Transdisciplinarity in Emergency Management

Transdisciplinarity in Emergency Management: From Whole-of-Society to Whole-of-Ecosystem

By Dr. Hayley Squance, PhD EM

Pioneering social psychologist Kurt Lewin once said, “You cannot understand a system until you try to change it.” That statement has been true throughout my work in animal emergency management (AEM), where I have experienced the complexity of integrating animal, human, and environmental needs into emergency management.

Animals have often been treated as an “add-on” in emergency management, something to be considered after the urgent work of saving lives and protecting infrastructure has been completed. Yet, lived experience in disasters reveals something very different: humans, animals, and the environment (H-A-E) are inextricably linked. People risk their lives for animals, environmental damage impacts both human and animal health, and community recovery is slowed when these interdependencies are ignored. These insights have shaped my own understanding of what it means to work across and beyond disciplines.

Understanding the Disciplinary Continuum

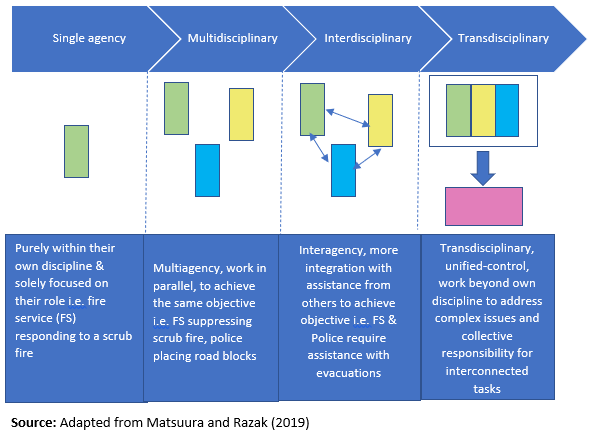

Collaboration in emergency management has long been described in disciplinary terms, including single agency, multidisciplinary, and interdisciplinary approaches, and more recently in disaster science as transdisciplinary (Figure 1).

Single agency approaches see each service working solely within its remit. For example, the fire service may respond to a scrub fire with no coordination with other agencies.

Multidisciplinary approaches involve multiple agencies working in parallel toward a common objective but with little integration. Fire services suppress flames, police place roadblocks, and each agency relies on its own intelligence and resources.

Interdisciplinary approaches increase integration and knowledge sharing. For example, fire and police might coordinate to manage evacuations, sharing information and resources while still operating within their disciplinary boundaries.

Transdisciplinary approaches transcend these boundaries. They bring together expertise to create unified, holistic solutions to complex, interconnected problems. Agencies move beyond their own roles, taking collective responsibility for interconnected tasks.

Figure 1. The disciplinary continuum from single agency to transdisciplinary collaboration.

Transdisciplinarity is not just about working together; it is about creating something new that no single discipline or agency could achieve on its own. In AEM, that has meant moving from including animals in planning to fully integrating H-A-E interdependencies across all phases of emergency management. More broadly, for the emergency management sector, it means evolving from fragmented action to ecosystem-level collaboration.

Why This Matters Now

Almost a decade ago, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015) called for a whole-of-society approach. Yet it is only recently that we have begun to see this language filter into emergency management practice. The truth is, the whole-of-society ship has already sailed. What is required now is a whole-of-ecosystem approach, one that explicitly acknowledges H-A-E interdependencies and works across boundaries to address them collectively.

The drivers are clear. Disasters today are increasing in frequency, intensity, and complexity. Climate change, population pressures, biodiversity loss, and globalised supply chains mean we can no longer afford to manage emergencies in silos. These issues are not only overlapping but compounding. A transdisciplinary, H-A-E-focused ecosystem approach equips us to reduce losses, protect livelihoods, and accelerate recovery by recognising that the well-being of people, animals, and environments is deeply interconnected.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a stark reminder of this. The origins of the virus, its rapid spread, and its long-tail social and economic consequences demonstrated how human health, animal health, and environmental conditions cannot be separated. In disaster contexts, whether floods, wildfires, cyclones, or pandemics, the same truth applies: interconnected risks demand interconnected solutions.

The Gap Between Principles and Practice

Frameworks such as New Zealand’s CIMS 3rd Edition (2019) are beginning to reflect H-A-E interdependencies, requiring that responses consider the needs of people, communities, and animals throughout the incident lifecycle. This is a significant step forward, signalling that animals and ecosystems are not peripheral but central to community well-being.

However, principles on paper do not always translate into practice on the ground. Many non-animal agencies still fail to recognise their role in the H-A-E interface. As a result, operational responses remain siloed mainly. During events, animal welfare organisations may scramble to coordinate with emergency services, often finding themselves marginalised in decision-making structures. Likewise, environmental impacts are often considered only after the human response is complete, despite their long-term significance for recovery.

This disconnection mirrors challenges experienced in other sectors. Public health, for example, has long grappled with disciplinary silos and has since developed transdisciplinary frameworks to integrate human, animal, and environmental health. Emergency management must now make the same leap.

What Transdisciplinarity Looks Like in Practice

Transdisciplinarity is often seen as an abstract or academic concept, but its application is very real. It demands:

Unified responsibility: Agencies move beyond “staying in their lane” to take collective responsibility for interconnected outcomes.

Shared intelligence: Data and information flow freely across agencies, creating a common operating picture that reflects H-A-E interdependencies.

Integrated problem-solving: Rather than aligning activities in parallel, agencies co-design solutions that reflect the complexity of the challenge.

Adaptive governance: Structures are flexible, enabling collaboration that cuts across organisational and jurisdictional boundaries.

In AEM, a transdisciplinary approach could look like human evacuation centres that are designed from the outset to accommodate animals, recognising that people’s safety is tied to their ability to keep their animals safe. In broader emergency management, it may mean that wildfire response plans integrate human evacuation, animal welfare, biodiversity protection, and water security into a single, coordinated operation, rather than four separate streams.

From Whole-of-Society to Whole-of-Ecosystem

When the Sendai Framework introduced the concept of a whole-of-society approach, it was a progressive call to action. But a decade on, our reality has shifted. Society is inseparable from its ecosystems. Our vulnerabilities and capacities are shaped as much by environmental conditions and animal health as they are by social and economic factors.

A whole-of-ecosystem approach moves us beyond tokenistic inclusion and into genuine integration. It is not about adding animals or the environment into existing plans, but about designing emergency management systems that reflect the true interconnectedness of our world. It is about seeing every disaster through the lens of H-A-E interdependencies and shaping responses accordingly.

Conclusion

Kurt Lewin was right, systems only reveal themselves when we try to change them. The attempt to integrate animals into emergency management has uncovered a more profound truth: we cannot manage disasters effectively without acknowledging and operationalising H-A-E interdependencies.

Transdisciplinarity is not an optional extra or a theoretical ideal; it is a fundamental approach to problem-solving. It is a practical necessity for emergency management in an era of compounding and cascading crises. By moving beyond disciplines, agencies, and silos, we can evolve from the current siloed approach to a whole-of-ecosystem paradigm. One that protects people, safeguards animals, and sustains the environments we all depend on.